Indigenous Knowledge Mobilization

This page will explain practical guidelines for sharing your results if you are a researcher working within an Indigenous community, with Indigenous methodologies or if you are just curious as to how to begin to approach sharing knowledge ethically within these situations.

The guiding principles offered on this page are meant to work as a starting point for researchers and partners to consider how they build meaningful relationships with the communities involved, as that is the foundation of working in Indigenous research.

Planning for Knowledge Mobilization Prior to Research

Within the academic field, researchers are expected to share their knowledge widely and to assure that it is useful for individuals, organizations and communities who can apply it to relevant policies, programs and practices. Within the context of Indigenous research and doing research with Indigenous communities, granting agencies and researchers must recognize that establishing relationships and outlining responsibilities at the beginning of a project are crucial.

When building a research project within this context, it is necessary that the community itself is equally involved in the research. The foundation of this kind of work lies in building relationships that are equal partnerships and friendships with the communities and their members. This assures that researchers alongside the community are co-designing research projects that from the beginning develop appropriate ways to share the co-generated knowledge.

Building meaningful relationships and assuring that knowledge sharing is done appropriately necessitates that any work done provides accessible, culturally relevant and socially needed benefits to all involved. Researchers, particularly those who are not a member of the community involved, will need to make sure that they are engaging in fulfilling a need that the community themselves have directly asked for. There must be an understanding that each community is unique, and it is paramount to remain mindful of the context, interests, values, needs and customs.

Researchers who do not come from the community that will be impacted by the results of the research should work to assure that they are being reflexive prior to engaging in the research itself.

The University of Warwick outlines reflexivity as:

“the examination of one’s own beliefs, judgments and practices during the research process and how these may have influenced the research. If positionality refers to what we know and believe then reflexivity is about what we do with this knowledge. Reflexivity involves questioning one’s own taken for granted assumptions.”

Some helpful reflexive questions to ask yourself before you get to the knowledge sharing process:

- What assumptions do I make about what constitutes valid and useful knowledge?

- How have/will my background and perceptions affected/affect the data I collect and the analysis of that data?

- With what voice am I sharing my perspective?

- Am I working in collaboration with the community by assuring the research is reciprocal?

- What audience am I collecting this data for, and how will they make sense of what I discover?

Chapter two of the 2020 UNESCO report written by Reed et al discusses how there are no set broad guidelines in place as to how foundations for knowledge sharing and mobilization across intercultural contexts should be approached, but that recognizing your position within the research before it has begun is critical to engaging with Indigenous people and communities in ways that assure ethical protocols are being met.

Ethical Guiding Principles for Knowledge Sharing

It is necessary for all researchers to be familiar with the following ethical frameworks and guidelines for working with Indigenous communities prior to engaging in research:

- Chapter 9 of the Tri-Council Policy Statement: Research Involving the First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples of Canada.

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action

- UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

- More Than a Checklist: Meaningful Indigenous Inclusion in Higher Education

- Research Ethics: A Source Guide to Conducting Research with Indigenous Peoples (page may be temporarily unavailable)

When working alongside Indigenous communities in research, there are two extremely helpful ethical frameworks to center in your interactions, methodology, and research design:

1. Indigenous Wholistic Framework.

This framework was developed by Michelle Pidgeon in 2016 and works to connect not only the philosophical elements of Indigenous knowledges but also show how complex the interconnections that we have as individuals are to those around us. This framework recognizes that thinking of research solely as an intellectual exercise ignores many key components in the learning process and who the knowledge affects.

The four ethical principles guiding this framework are:

- Respect

- Reciprocity

- Relevance

- Responsibility

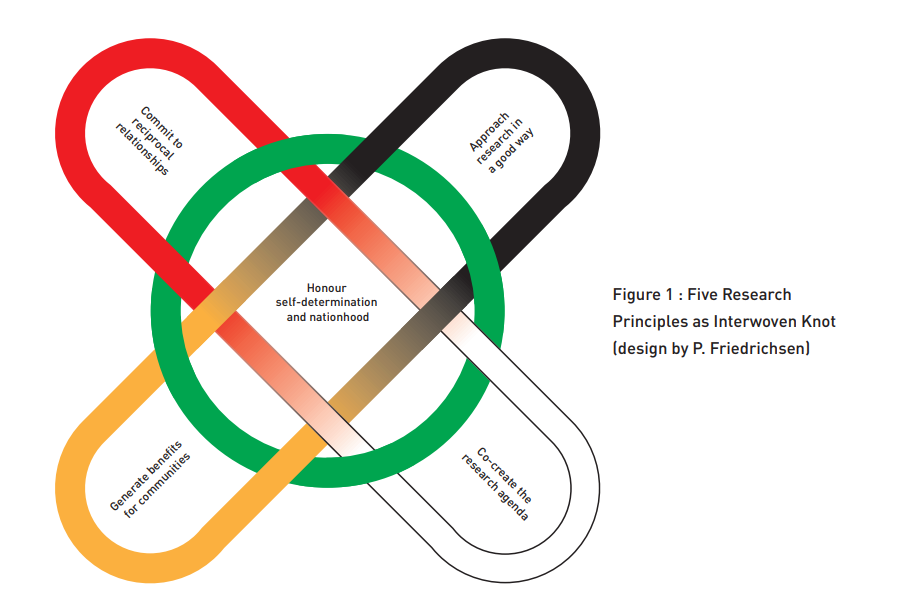

2. Five Research Principles as Interwoven Knot

This framework visualizes how the five principles of doing research are bound and interlinked. The use of the colors and the circular relationship between them were designed to honor the Medicine Wheel used by numerous Indigenous peoples in North America. The knot design is a traditional Celtic symbol chosen intentionally to signify the weaving of diverse cultures through respectful, reciprocal and ongoing collaboration.

The five ethical principles guiding this framework are:

- Honor self-determination and nationhood

- Commit to Reciprocal Relationships

- Co-Create the Research Agenda

- Approach Research in a Good Way

- Generate Benefits for Communities

Both of these frameworks to approach working with Indigenous communities in research discuss the importance of building reciprocal relationships, and the responsibility of all members of the research being active agents in the research agenda. If you are going to approach a research project with an Indigenous community, it is also very important that you are aware of the frameworks within that specific community and center them in the design of the project.

There are distinct understandings of knowledge and unique contextually specific knowledge sharing processes within each Indigenous community, and because of this each community will have set protocols for sharing knowledge as well as determining which knowledge is for the public eye. It is also important when working with Indigenous communities that the researcher is aware of the level of Ownership, Control, Access, and Possession of data that has been determined appropriate by the community (First Nations Information Governance Centre 2019).

Sharing Research Results

Research findings should be shared in ways that are culturally relevant and in formats that are functional, useful and practical to the community. Some examples of ways that this can be done include:

- Short, plain language reports

- Products in Indigenous or local languages

- Creative visual or video materials

- Skill sharing workshops

Prior to the research being completed, agreements will have already been made with the community as to which organizations or key stakeholders will have access to the data. These stakeholders should always be directly identified by the community, and may include open access outlets, community contributors, academic outputs such as conference publications, as well as Indigenous run conference presentations.

Some examples as to how this has been done in prior research include:

1.MIIJIM: TRADITIONAL FOODS OF THE ANISHINAABEG

The development of this exhibit was undertaken by research partners and Elders, Museum curators and public education staff as well as University researchers. This display was later produced as a digital booklet that the community could utilize surrounding the topics of language, food security and nutrition programs.

To see the full project please visit: https://themusekenora.ca/exhibit/miijim-traditional-foods-of-the-anishinaabeg/

2. Youth led Knowledge Sharing – Food Forest

The youth of Muskeg Lake Cree Nation created posters to showcase the ideas they had for their communities food forest initiative. These posters were later presented to the local Food Security Committee and Elders who had the authority to implement these ideas and develop a food forest. The posters are an example of community generated and owned data, as well as new forms of knowledge exchange between youth and elders.

To learn more about this project please visit: https://muskeglake.com/reimagining-food-forests-from-food-security-to-food-sovereignty/

3. Celebrating Salish Conference

This conferences goal is to promote new speakers of the Salish language family, collaborate with other Indigenous communities and build ongoing relationships with one another. One way that this is done is through a presentation of findings from language revitalization efforts and research that have taken place through community collaboration. These presentations take the form of a discussion of research and then a teaching presentation to show the practical applications of research.

To learn more about this conference please visit: https://kalispeltribe.com/our-language/celebrating-salish-conference/

These are just three examples out of endless possibilities that show how knowledge obtained through research can be presented and utilized. Good practices for Indigenous knowledge mobilization happen when researchers engage with partners in a relationship of knowledge co-creation.

By aiming to foster long-term, positive, and reciprocal relationships, research can be transformed into relevant and long lasting results that creates change for all involved.

Upholding Your Commitment to Reciprocity

Sharing the results from the research that has been done is one part of knowledge mobilization, but it is not the only important aspect. As researchers become familiar with a specific community and their needs, they can identify opportunities for giving back to the community who has supported their academic research and personal growth.

Benefits that can be shared with the community must be personalized to the researchers involved and tied to their unique skills and talents. Examples of knowledge sharing that researchers can participate in include:

- Providing training of individual community members in specific skillsets

- Mentoring youth

- Assisting youth in connecting to appropriate post-secondary institutions

- Training exchanges

- Teaching demonstrations

- Skill sharing events

- Facilitating Intergenerational community skill sharing

When working with the community to design the project outline, it will become clear as to how you as an individual researcher can give back in tangible ways that help to generate benefits for the community.